Fracking has been hailed as a successful strategy in the energy sector: it has helped decrease natural gas prices while boosting electricity production from natural gas beyond coal, thereby enhancing air quality. States that initially adopted unconventional natural gas development via fracking have noted potential benefits economically, in energy, and for communities. However, communities where fracking spread quickly voiced apprehensions about the process. Residents nearby reported various symptoms and stress-induced issues. Public health experts expressed their worries, prompting epidemiologists to investigate the industry’s health impacts. States like Pennsylvania, with nearly 10,000 wells drilled since 2005, proceeded with development.

However, Maryland and New York have restricted drilling due to its possible environmental and health implications. The tension between economic growth, energy policy, and environmental and health issues is a recurring theme in public health history. Often, economic and energy growth overshadows environmental and health issues, leaving public health efforts to catch up. Only recently have thorough studies been completed on unconventional natural gas development’s effects on health. We’ve published three studies examining birth outcomes, asthma exacerbations, and symptoms like those affecting the nasal and sinus areas, fatigue, and migraine headaches. Combined with other research, these form a growing body of evidence indicating that unconventional natural gas development has detrimental health effects. Predictably, the oil and gas industry has sharply criticized our findings.

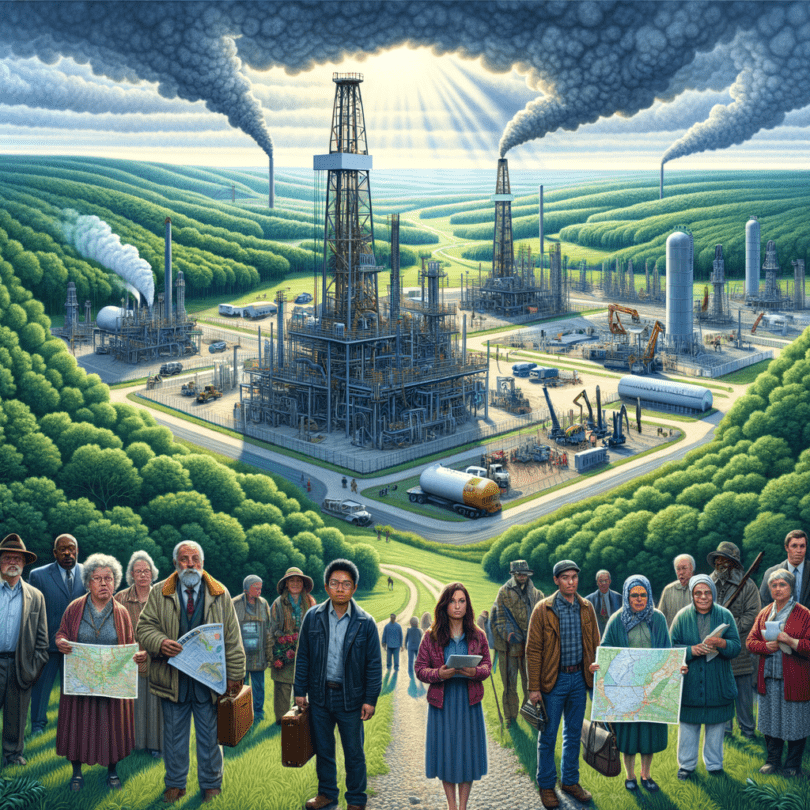

Fracking involves both vertical and horizontal drilling, typically reaching depths exceeding 10,000 feet, followed by the high-pressure injection of millions of gallons of water, chemicals, and sand. This process creates fractures that enable the release of natural gas from shale rock. As fracking became economically feasible, oil and gas companies moved into communities with shale gas resources, resulting in various local effects. Communities near fracking sites might experience disruptions such as noise, light, vibrations, and truck traffic, alongside pollution affecting air, water, and soil.

The industry’s rapid expansion can also lead to social disturbances, increased crime, and heightened anxiety. These effects differ across well development phases and vary in impact: vibration may affect only those close to wells, whereas stress from potential water contamination concerns could be more widespread. Other stress factors include the arrival of temporary workers, industrial developments in previously rural areas, heavy truck traffic, and worries about decreasing property values.

In collaboration with the Geisinger Health System, which provides primary care to over 450,000 patients in Pennsylvania, many of whom are in fracking areas, we conducted multiple health studies. Geisinger has employed an electronic health record system since 2001, enabling access to detailed health information from all patient visits, covering diagnoses, tests, treatments, medications, and more during the fracking boom. In our initial electronic health record-based studies, we focused on adverse birth outcomes and asthma exacerbations, given their importance, commonality, short latency periods, and the fact that affected individuals typically seek medical care, ensuring documentation in electronic health records.

Our research encompassed more than 8,000 mother-child pairs and 35,000 asthma patients. In our symptom study, we surveyed 7,847 patients about nasal, sinus, and other health issues. Because symptoms can be subjective and not easily documented in electronic health records, questionnaires proved more effective for gathering this data. In all our studies, we assigned unconventional natural gas development activity measures to patients. These measures were calculated based on the distance from a patient’s home to the well, well depth and production levels, and the timing and duration of various development phases.

In the study on birth outcomes, we observed an increased likelihood of preterm births, and indications of reduced birth weights among women exposed to higher unconventional natural gas activity (those living closer to larger and more numerous wells) compared to those with lower exposure during pregnancy. The asthma study revealed increased chances of hospitalizations, emergency room visits, and usage of medications for mild asthma attacks among patients in areas with higher activity compared to those in regions with lesser activity.

Our symptom study showed that individuals in high-activity areas reported more nasal and sinus symptoms, migraines, and fatigue than those in lower activity zones. Each analysis accounted for other risk factors like smoking, obesity, and existing health conditions. Psychosocial stress, exposure to air pollution from truck traffic, sleep disturbances, and socioeconomic shifts are potential ways through which unconventional natural gas development may impact health. We hypothesize stress and air pollution as the main pathways, but our current studies cannot definitively attribute the observed associations to these factors. As epidemiologists, our data rarely proves that an exposure directly leads to a health outcome.

However, we conduct further analyses to ensure our findings’ robustness and that no omitted factor could cause them. We examined differences by county to determine if unique population characteristics in fracking versus non-fracking areas influenced results, and replicated our research for other health outcomes unlikely to be impacted by fracking. None of our analyses suggested any significant bias, bolstering our results’ credibility. Other researchers have also studied pregnancy, birth outcomes, and symptoms, presenting a growing body of evidence that fracking might be affecting health in multiple aspects. Over time, the evidence has become clearer, more consistent, and troubling. While not all studies are expected to align perfectly because of differing drilling methods, health conditions, and other variables in diverse study settings, this complexity doesn’t invalidate our findings.

The industry often argues that unconventional natural gas development improves air quality. This might be true on a national scale, but these statements overlook studies suggesting worsened local air quality in fracking regions. The industry commonly counters that instances of health issues like asthma or preterm births are lower or declining in fracking areas compared to non-fracking ones. Studies examining disease rates over time across groups are termed ecological studies. These are less revealing than those with individual-level data since group-level relationships might not reflect individual-level realities, known as the ecological fallacy.

For instance, ecological studies might show a negative link between average county radon levels and lung cancer rates, but individual studies exhibit a strong positive link between radon exposure and lung cancer. We used individual-level data in our peer-reviewed research to avoid the ecological fallacy. Therefore, the industry-reported rates do not challenge our findings. It’s noteworthy that the fracking industry’s practices have improved over time. For instance, well flaring, a contributor to pollution and noise, has significantly decreased. Drilling has also slowed due to the sharp drop in natural gas prices. Every energy decision carries both advantages and disadvantages. Particularly for Maryland, with its fracking moratorium ending in October 2017, decisions lie ahead. Continuous health monitoring and detailed exposure assessments, such as measuring noise and air pollution, are necessary. Understanding why the fracking industry correlates with health issues will enable better guidance for patients and policymakers.